CLEM Applications

Selected examples of CLEM usage at ScopeM are listed below.

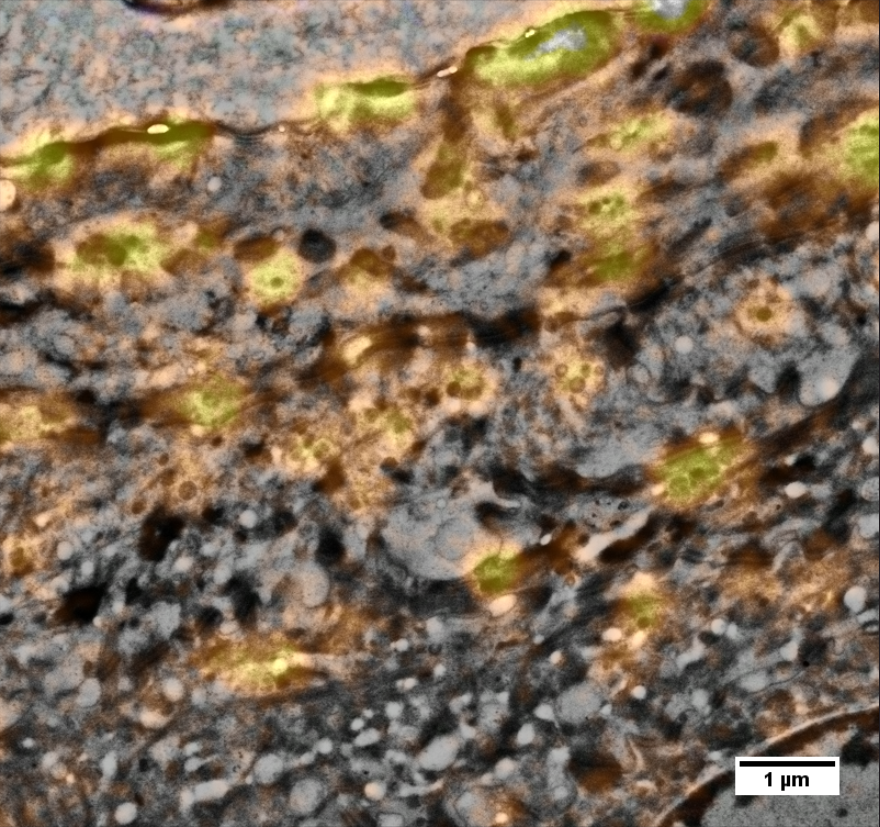

Volume CLEM - Fluorescence-Guided FIB-SEM to Investigate Selective Autophagy in Virus-Containing Endosomes

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is an oncogenic γ-herpesvirus. During infection, the autophagy protein LC3B co-localizes with KSHV in amphisomes, showing that autophagosomes fuse with virus-containing endosomes. Reducing autophagy-related proteins increases KSHV infection, indicating that macroautophagy helps protect cells Using a recombinant virus expressing mScarlet coupled to the small virus capsid protein encoded by ORF65, we tracked KSHV infection in U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Autophagosomes were identified via GFP-tagged LC3B which gets covalently attached to autophagosomal membranes. Since in confocal data, only about 15% of KSHV mScarlet puncta co-localized with GFP-LC3B an orchestrated correlative approach was indispensable (external page Schmidt et al., 2024).

Cells are grown in glass-bottom dishes with a gridded coverslip containing an alphanumeric pattern. Regions of interest (ROI) are identified through confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, followed by samples preparation for EM and embedding in resin. In the FIB-SEM, the ROI is relocated using the alphanumerical pattern of the coverslip.

Mitochondria labeled with MitoTracker Deep Red served as internal fiducials for image alignment and correlation. See the full protocol: external page Lucas et al., 2025)

(A) Aldehyde-fixed cells were imaged with confocal microscopy to identify target cells. Amphisomes were identified by co-localization of mScarlet labeled ORF65 from recombinant KSHV (magenta) with the autophagosomal marker LC3B-GFP (green), appearing as yellow. MitoTracker Deep Red (cyan) served as an internal fiducial marker for precise correlation with FIB-SEM data.

(B) Overlay of MitoTracker Deep Red signal on an x-z projection of the correlative FIB-SEM data.

(C) Overlaying co-localized mScarlet:ORF65:KSHV and LC3B-GFP signals onto the FIB-SEM image stack identifies the precise location of an amphisome. The enlarged detail (corresponding to the boxed region in the left image) shows a cross-section of an amphisome with a virus particle at the bottom.

(D) shows a 3D reconstruction of this amphisome with KSHV in red, lipid-rich structures in yellow, and intraluminal structures in blue.

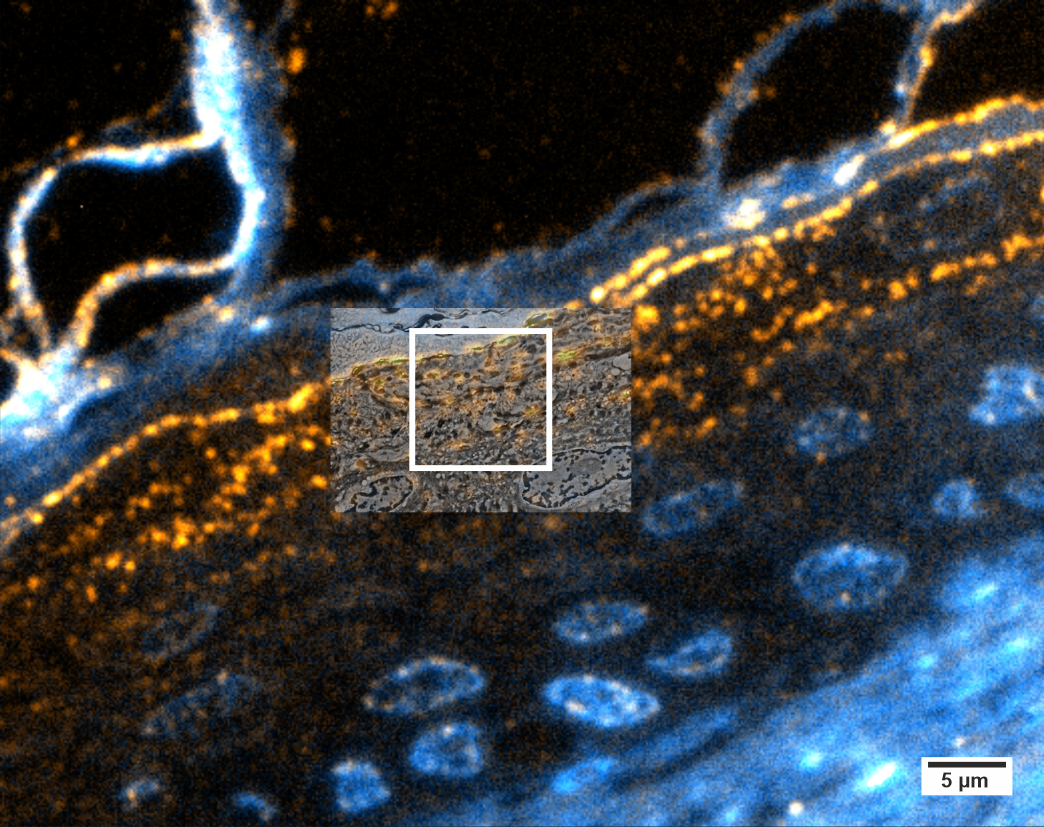

Immunolabeling as a tool to identify the ROI for high-resolution SEM

Here, a resin section of human skin was labeled for glucosylceramide (orange), a sphingolipid involved in mitogenesis and final epidermal differentiation. The skin sample was high-pressure frozen and freeze-substituted in the presence of uranyl acetate and finally embedded in HM20 acrylic resin. 100 nm thick sections were mounted on ITO- coated coverslips, a transparent, but conductive support well suited for correlative imaging in LM and SEM. Immunofluorescence shows the localization of glucosylceramide in lamellar bodies in the stratum granulosum and upper stratum spinosum, accounting for the typical bead chain- like pattern once exported into the intercellular space at the interface to the stratum corneum. Nuclei were stained with Dapi (blue).

The ROI was relocated in the SEM using “Zeiss Shuttle & Find.” The enlargement (position marked by white frame in upper image) shows an overlay image of fluorescence signal and SEM. It demonstrates the difference in imaging resolution of the two microscopy modalities: while the fluorescence signal shows rather large ovoid shapes of approx. 500 nm in diameter, the SEM image reveals clusters of up to five vesicles or lamellar bodies no larger than 100–200 nm where only one fluorescence spot is detected. It even exposes vesicles that have no corresponding fluorescence spot at all (external page Lucas et al., 2012).

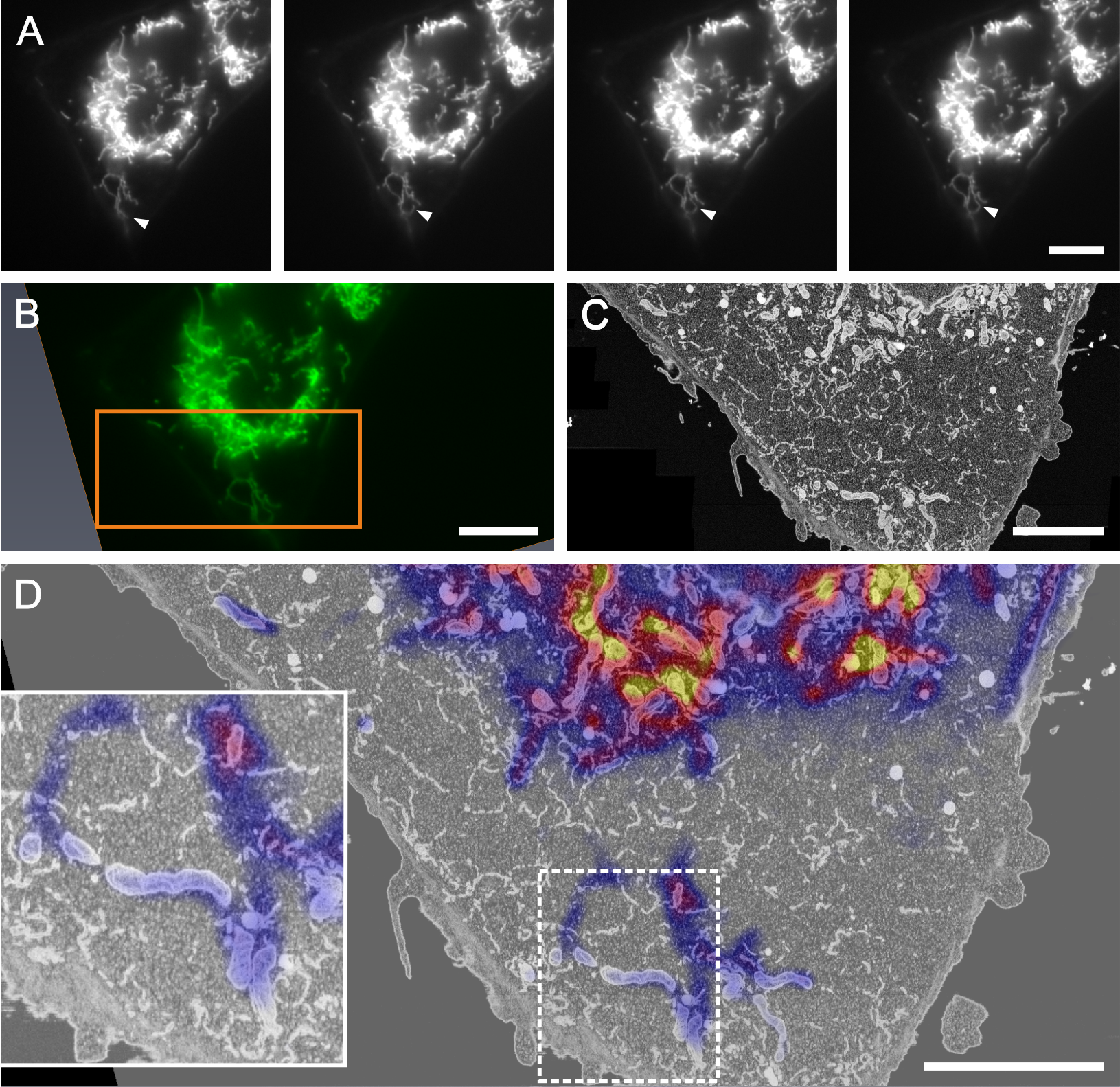

Correlative live cell imaging and FIB-SEM

Correlation of live-cell TIRF imaging with FIB-SEM using a U2OS-derived stable cell line co-expressing a mitochondrial and an endoplasmatic reticulum marker (courtesy of Prof. Dr. Benoît Kornmann; external page Kanfer et al., 2015)

(A) A time-lapse series of TIRF images was acquired capturing the movement of mitochondria (arrowhead) over 100 s (at 0, 30, 60, and 100 s from left to right), then at the time of interest the sample was chemically fixed.

(B) TIFR image of the same ROI after chemical fixation. After preparation for EM (heavy metal contrasting, dehydration and resin embedding) the same ROI was relocated and a FIB-SEM volume of this cell was recorded (position marked by orange rectangle).

(C) Virtual slice of the FIB-SEM volume matching the primary imaging orientation of the TIRF images to facilitate the correlation.

(D) Overlay of images B and C: the LM overlay is depicted using a lookup table ranging from blue to yellow for better visibility. Here, the resolution mismatch of the two imaging techniques becomes apparent: The FIB-SEM dataset has a much finer depth-resolution (8 nm isotropic voxels) compared to the TIRF image, therefore fluorescence signal recorded in a single imaging plane in LM is generated from a larger volume (z-resolution 200 µm), explaining the fluorescence signal in areas where no mitochondria are depicted in a single virtual slice of the FIB-SEM stack (inset).

Further details see external page Lucas et al., 2017.